Introduction

Location Map

Base Map

Database Schema

Conventions

GIS Analyses

Flowchart

GIS Concepts

Results

Conclusion

References

Risk Assessment of Rabies in the Ethiopian Wolf (Canis simensis)

Abby Flory & Jessica Healy

NR505 Group Project

Bale Mountain National Park (BMNP) in southern Ethiopia is a protected area of mainly Afroalpine vegetation that houses 24% of Ethiopia's mammalian species, including the endangered mountain nyala (Tragelaphus buxtoni) and the Ethiopian wolf (Canis simensis) (Hillman, 1993).

Domestic dogs are the most abundant carnivore in Bale Mountains National Park (BMNP) in Ethiopia at a density of 6.4 dogs per square kilometer in the highlands, and at 2.2 dogs/km2 in the lowlands. In the villages surrounding BMNP, 44% of households own dogs, and of these, 8% own more than one dog. These dogs are used to protect herds of livestock from hyenas, and many are semi-feral. However, there is another canid inhabiting the highlands of BMNP, the highly endangered Ethiopian wolf (Canis simensis). This coyote-sized carnivore feeds exclusively on diurnal small mammals, including the giant molerat (Spalax giganteus), grass rats (Arvicanthus niloticus), and Stark’s hare (Lepus starcki).

As such, wolf abundance is closely correlated with rodent biomass in BMNP. Wolves primarily inhabit habitats that support high rodent biomass, specifically areas that have short vegetation with afroalpine herbaceous communities, but also montane grasslands and ericaceous heathlands. However, areas of high rodent and wolf density also correspond to areas ideal for grazing local cattle, and with the cattle come dogs. These dogs are the main source of rabies in BMNP, and also cause problems with hybridization in the wolf population. Since wolf packs are typically made up of one reproductive pair and several related non-alpha members, the non-reproductive females may breed with the feral dogs and produce hybrids that tend to outcompete the purebred wolves.

In the central highland zones alone, there are about 8813 million cattle, 4606 million sheep, 3393 million goats, 1214 million asses, 606 thousand horses and 72.6 thousand mules (Central Statistical Authority, 1998). Since good forage is often scarce, many pastoralists graze their animals in the BMNP. Some data suggest that cattle compete directly with rodents for food, and as such, high densities of grazing cattle may decrease rodent biomass, which is the prey base of wolves in BMNP (Stephens et al, 2001).

The purpose of this project is to predict areas of high risk for exposure of C. simensis to rabies carried by domestic dogs. To accomplish this, we will employ various GIS tools in order to demonstrate the facility of this program for use in conservation planning.

Population structure:

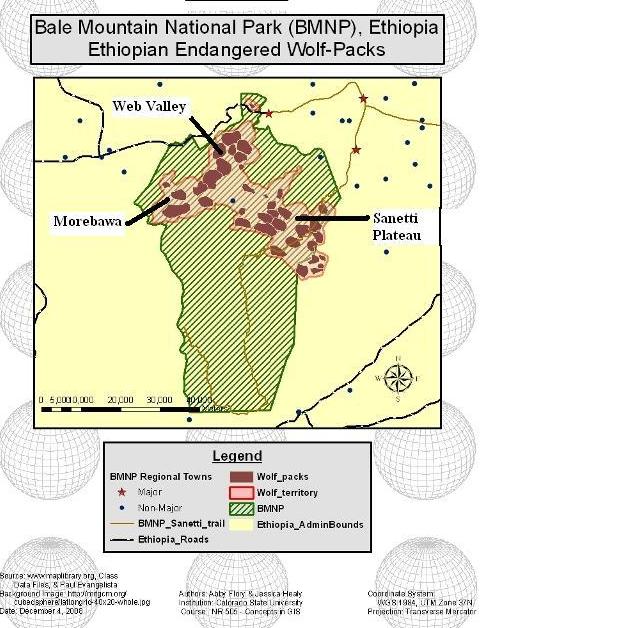

Three main wolf subpopulations exist in BMNP—one in the Web Valley (~95 individuals), one in Morebawa (~111 individuals) (Haydon et al 2006), and one on the Sanetti plateau (~79 individuals) (Williams 2005).

The subpopulations are connected by narrow corridors of appropriate habitat, and other packs are spread throughout viable habitats in the park. Each pack consists of 2-13 individuals, with home-ranges covering from 2-15 km (Sillero-Zubiri & Gottelli 1995). Population density varies with habitat quality, ranging from 1-1.2 adults/km2 in areas of high rodent biomass to 0.1-0.2 adults/ km2 in less optimal habitats (Sillero-Zubiri & Macdonald 1997). Optimal habitat for Ethiopian wolves is rolling grasslands and valley meadows dominated by short herbs and grasses, including Alchemilla abyssinica, Polygonum plebejum, Trifolium acaule, Anthemis tigrensis, Artemisia schimperi and Poa muhavaurensis (Miehe & Miehe 1994).

Rabies in the Ethiopian wolf:

The Canid Type 1 rabies virus is endemic in Ethiopia; domestic dogs are the only known reservoir for the disease in the Bale Mountains (Randall et al 2004). Two large outbreaks of rabies occurred in the Ethiopian wolf population in 1992 and 2003, causing population crashes. 77% of known wolves died or disappeared from 1991-1992 (Sillero-Zubiri et al 1996), and 76% of the wolf population in the Web Valley succumbed from 2003-2004 (Haydon et al 2006). Since domestic dogs are the reservoir, efforts have been made to vaccinate local dog populations, resulting in ~70% vaccination coverage. However, in 2003, the outbreak was probably caused by an unvaccinated immigrant dog accompanying people and cattle looking for seasonal grazing (Randall et al 2004). Clearly, simply vaccinating local dogs is insufficient for controlling rabies in the Ethiopian wolf.

Vaccination strategies:

When attempting to control outbreak of a disease, two vaccination strategies can be employed: one focuses on eliminating disease entirely from a population while the other focuses on protecting an endangered species from extinction by vaccinating only a certain part of the population, thereby restricting the impact of large outbreaks that might bring the population below a viable level (Haydon et al 2006). Researchers in BMNP received permission to employ a reactive vaccination strategy during the 2003 outbreak—since oral rabies vaccines are not yet licensed for use in Ethiopia, parenteral (in this case, intramuscular injection) vaccination was used to directly protect wolf packs (Randall et al 2004). Wolves were captured using rubber-lined leg hold traps, anesthetized, immunized, and administered with long-acting antibiotics. The 2003 rabies outbreak started in the Web Valley subpopulation, and was most destructive there; due to the advanced stage of the outbreak, the vaccination teams chose to focus on the other two subpopulations. A total of 77 wolves were captured and vaccinated, mainly along the corridors of good habitat and ‘front line’ territories connecting the three subpopulations. The strategy seemed to be effective—the last known rabies case was found in the Web Valley in January 2004, and no rabies-related deaths were found in the intervention area (Knobel et al 2008).